Building a Crowdsourced Food Database

"An app like this ultimately lives or dies by its database, no matter how “elegant” it may otherwise be." ★☆☆☆☆ – App Store User Review, November 2019

The hardest part of building a food tracking app is obtaining nutrition data. It's not because there aren't options. There's several nutrition data API services who would gladly sign you up as a customer.

For an indie developer like myself, signing up for an API to power your app isn't an easy decision. All services are going to have some strings attached. Most options are off the table, simply because they are too expensive. Some have restrictions on how the data is viewed and presented, which impose on the user experience. Some options would only work if I eliminate the FoodNoms free tier, therefore removing a critical piece of my marketing strategy. Some have great data for products in the USA, but don't have great data internationally.

For larger companies with funding or serious revenue, the cost is manageable. Still, what company wants to outsource a core piece of their product?

I had been considered building a food tracking app for years before I broke ground on FoodNoms in 2019. Each time I thought about it, I would always dismiss the idea. I thought to myself, "there's no way anyone would be interested unless it had a huge food database like MyFitnessPal."

As I kept using other food tracking apps, my frustration with their slow, user-hostile design grew over time. Eventually, this frustration crossed a threshold to where I didn't care anymore about food database. I figured that even though I would likely be unsuccessful, it's still worth trying.

The world needs better food tracking apps. Apps that are focused on the user experience; prioritizing privacy, simplicity, and actually helping people improve their nutrition and their lives.

Over the past six months since launching FoodNoms, I've learned a lot more about how others think about food databases. People tend to have a hard time describing why a food database is bad. But they know it when they see it.

It's clear that FoodNoms' database was not cutting it for many folks. I've been wanting to find a solution to this problem for months, and I've considered many different creative solutions. In the end, I decided to go with what felt right. I'm going to build it myself.

Leveraging The App's Nutrition Label Scanner

One thing I've learned over the past six months is just how lucky I was to build FoodNoms the same year that Apple release its OCR Vision framework. I originally built the feature on a whim one weekend, thinking that it likely wouldn't be good enough to ship.

Turns out, had I not built that feature, I most likely wouldn't still be working on FoodNoms today. The nutrition label scanner has not only made up for my main weakness, it ended up turning into a strength. I've even received several notes from customers saying that the scanner is their favorite feature.

When I decided to move forward with the crowdsourcing strategy, I knew that the most of the data would originate from the nutrition label scanner.

While the scanner was a wonderful feature, it still felt like a lot of work to use. Not because of the scanner itself, but because of the tedious steps required to do everything else required to create a new food item:

- First, tap the tiny barcode icon and scan the product to see if it already exists

- Be disappointed and tap the "Create New Food" button

- Enter the product name and brand

- Enter the serving size on another screen

- Scan nutrition label and tap the done button when finished

A month or so ago I had an a-ha moment when I was using the scanner: what if the app seamlessly transitioned from search to creation?

Thus led to the design of the new unified barcode + nutrition label scanner. The new flow for searching/creating foods requires less tapping and context switches. Here's a video recording of the new flow in action:

Here's a preview of the next iteration of the @food_noms scanner UI. If the food isn't already in the FoodNoms DB or "My Foods", it's a seamless transition from scanning the barcode to the nutrition label. pic.twitter.com/vk0iiYbdEj

— Ryan Ashcraft (@ryanashcraft) May 10, 2020

I made several other improvements to the creation experience, in order to minimize friction and maximize data quality.

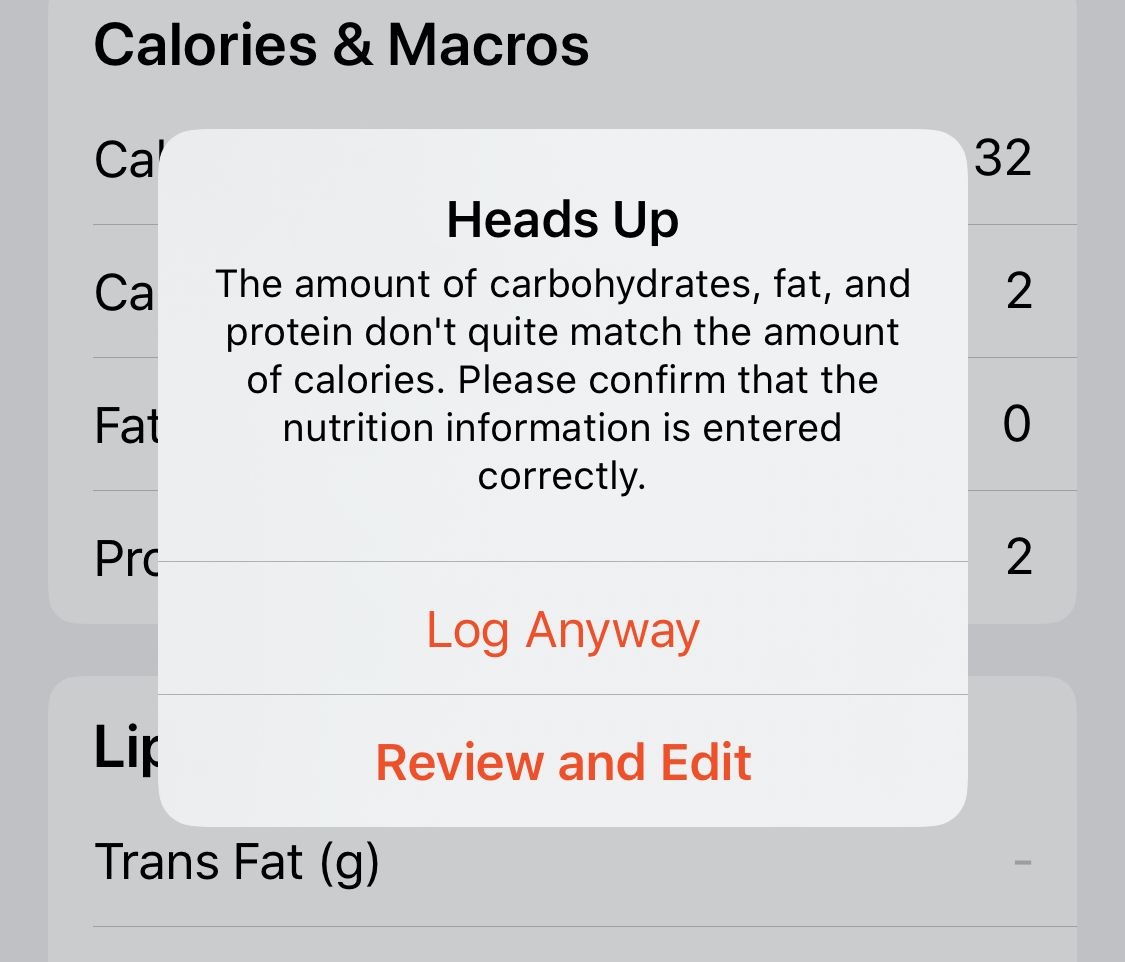

The most significant change is to the serving size input. What was previously three six inputs strewn across three separate views is now two just inputs. I've also implemented a user suggestion to be able to tab up and down between the numerical inputs, as well as a basic energy/macros validation check.

Designing for Data Trust

One of the common criticisms of some other food databases that have crowdsourced data is that they err on the side of quantity over quality. I wanted to take a different approach with FoodNoms.

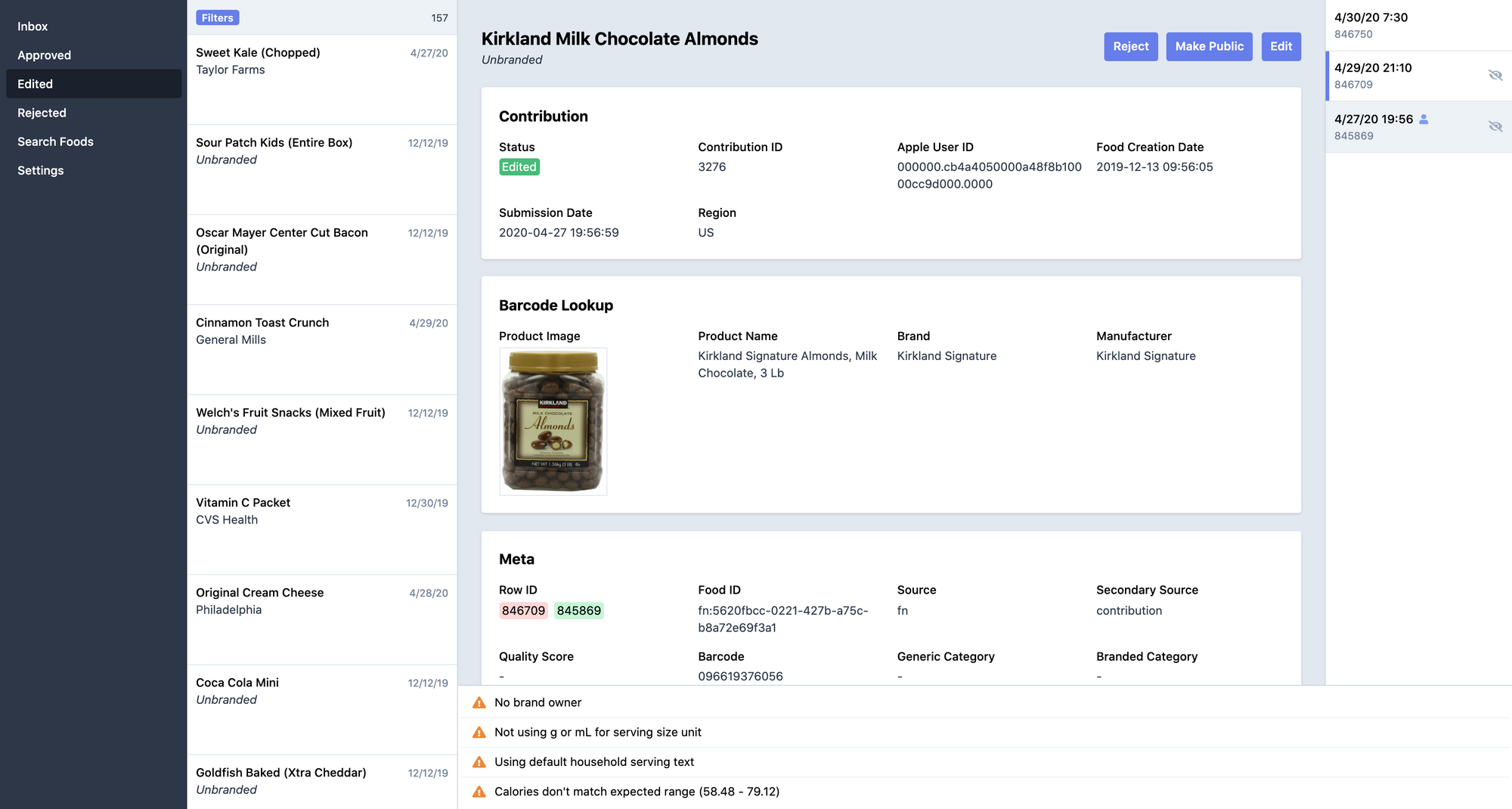

I am requiring that all foods have barcodes, which I use as a common unique identifier. I am also starting out by manually approving each food myself. This will undoubtedly be a burden (it already is to some degree). However, by manually approving each food, I can better understand what issues exist and how I could scale/automate the process.

The key feature of my moderation tools is the ability to filter by possible issues like missing the brand owner field, calories not matching macros, outlier nutrient values, and invalid barcodes. I'm also experimenting with an (affordable) barcode metadata API for an additional datapoint.

I offer no guarantees in terms of the turnaround time for food submissions. It could be hours, days, or weeks. But I don't need to commit to any timeline. Users that submit foods already have a copy on your device and can share it with friends and family via AirDrop or direct message. The only one that's suffering from slow review times is myself.

Designing for User Control

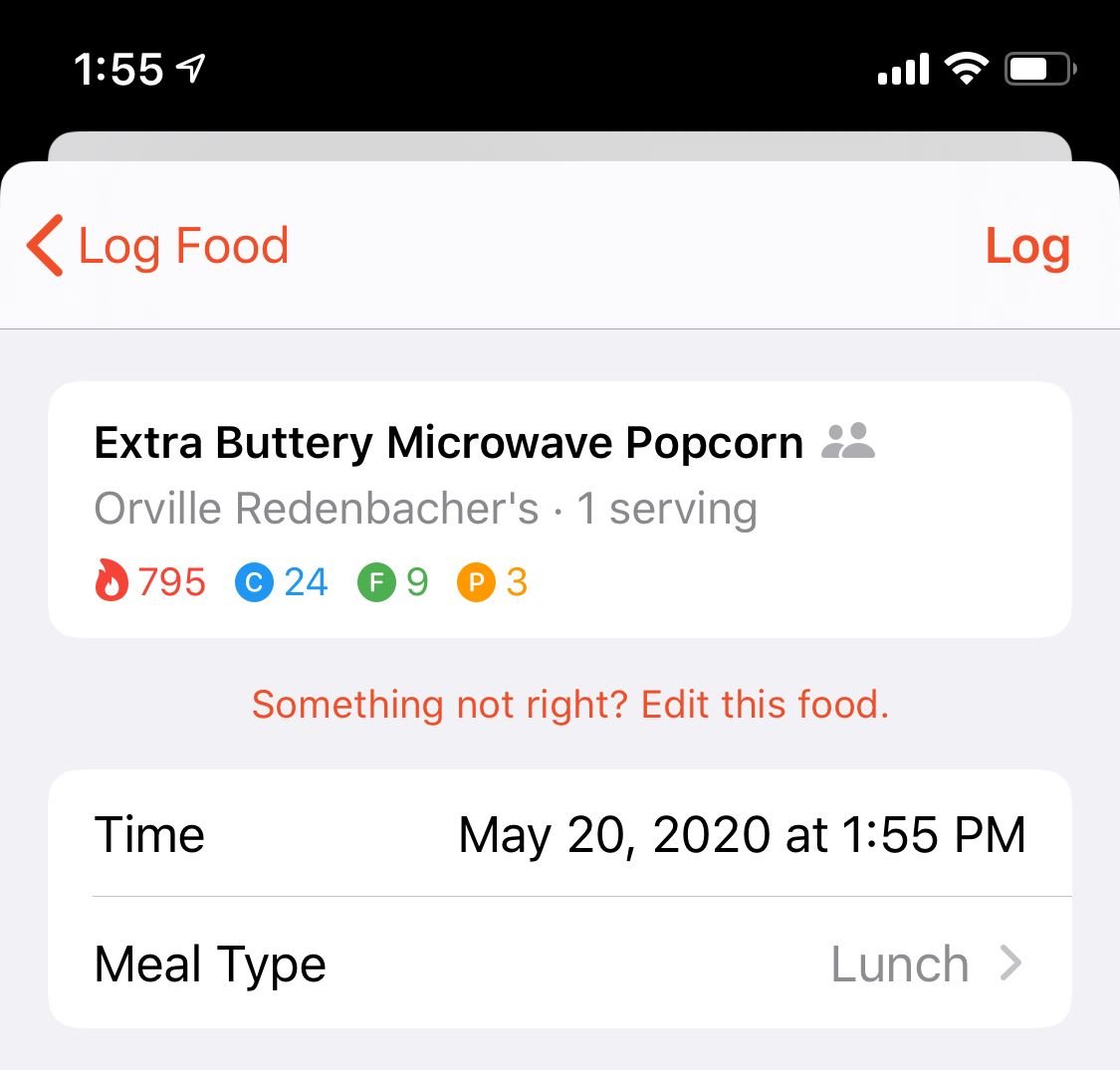

Even though I am moderating each food contribution, I won't be able to catch everything. I've also learned that unfortunately some of my existing data from the USDA has incorrect values at times. This inspired me to build a new option to edit branded search results:

If you are signed into the Community Database, then those edits will get sent back to me to review. In the meantime, next time you scan that food, it will use the copy that you edited instead of the one from the database!

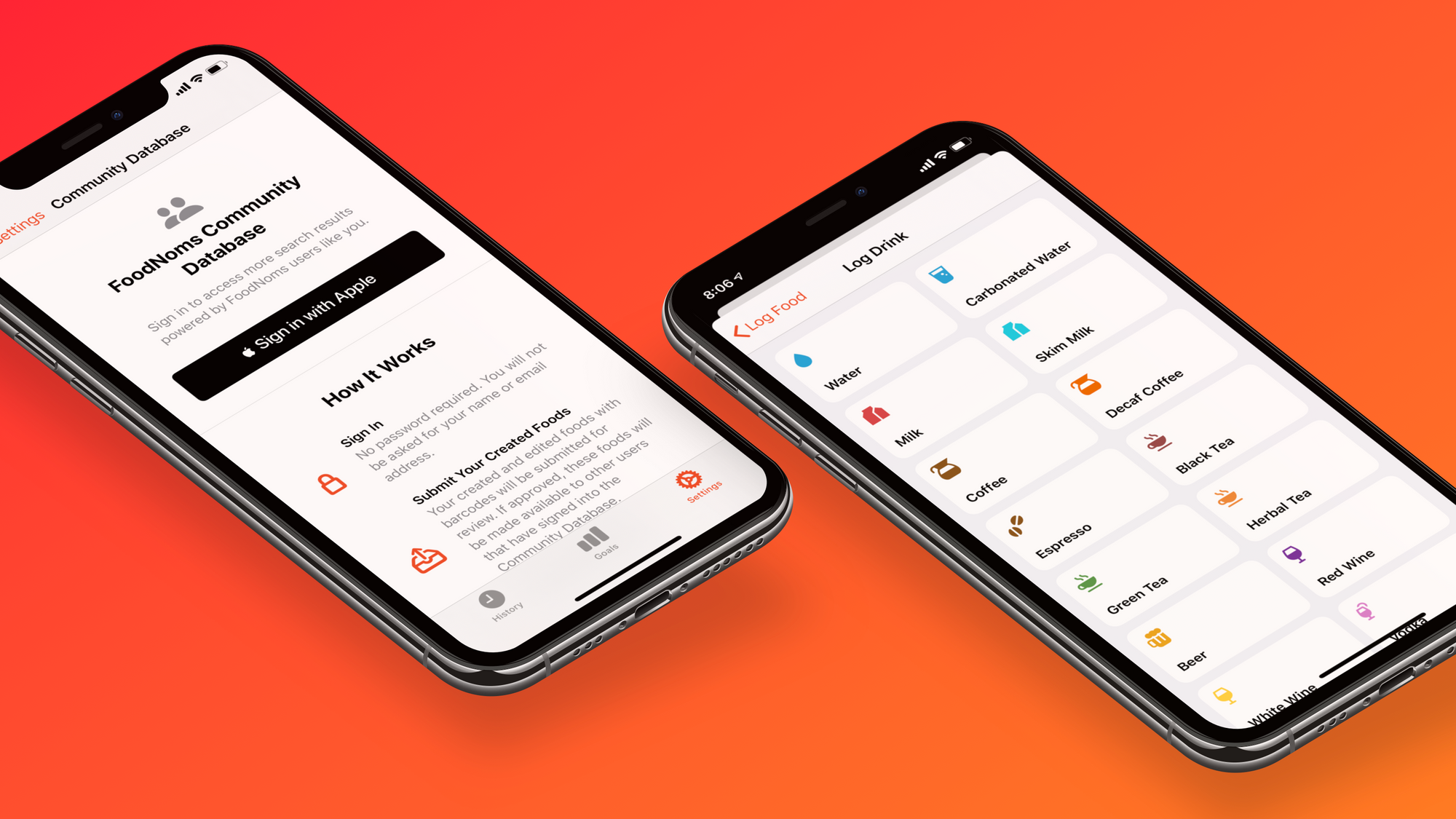

I've also made the Community Database an opt-in experience. If you don't want to contribute foods for whatever reason, you don't have to use this feature. The only downside is that you get any crowdsourced data. After you opt-in, by default you will be prompted with each new and edited food on whether you would like to contribute or not. If you would rather not be asked, you can also choose to always submit, or show a less-intrusive toggle UI instead.

Designed for Privacy

One large concern I had with opening up the database for crowdsourced submissions was security. How could I design the system so that I had only real users upload foods with an anonymous, trustworthy identifier?

My solution was to adopt Sign in with Apple. This new service from Apple is fantastic – it gives me a signal as to whether a user is "real" or not, without needing to ask for personal information. Sign in with Apple is already praised for its privacy advantages, like its ability to anonymize and forward email addresses. Turns out it can do even better. The app can decide not to even ask for an email address or name, and it still works as designed! Now I have a trustworthy user identifier from Apple, with an end-user experience for signing in is as seamless as possible.

Engineered for Speed

I believe one underrated aspect of FoodNoms is its incredibly-fast, as-you-type, search experience. Compared to some other food tracking apps I've used in the past, the difference is night-and-day. I knew that with all of these changes, I didn't want to regress on this front.

A food database doesn't require a sophisticated backend architecture to be fast. Currently, I'm using a straightforward stack with Nginx, Node, and Postgres hosted on AWS (RDS).

One large architectural change I had to make was to make public food identifiers non-unique, as there could be multiple edits of the same food with only one public version.

One new Postgres feature that I'm using as a part of these changes is materialized views . Unlike regular views, materialized views do not incur additional runtime cost, as the query results are precomputed.

(Postgres continues to amaze me.)

Optimizing Search Rankings

Another huge change I made as part of this release was making tweaks to the database to improve search rankings for generic foods. I shared some results on Twitter, but I'm really proud of how much I was able to improve the results with just a day's worth of work. This gives me even more confidence that with some work, I am capable of creating a quality food database experience.

Retaining Control of My Product

Deciding to go this route wasn't an easy decision. I agonized for hours/days/weeks, going back-and-forth on what to do. Today, I'm more confident than ever that this is the right path for me to take. Not just because of the reasons I have already mentioned, but because it closes the least amount of doors.

One alternative I considered was to partner with the folks working on Open Food Facts . While I am seriously impressed with what they've built and love their mission, I couldn't find a way to make it work. As part of their license, they require that no external non-public data can be used in the app. This means that down if I ever add any sort of non-public data to the app, I would need to simultaneously completely remove their API/data. I completely understand why they have this restriction, but it's not something I want to be bound by.

At the end of the day, building my own database gives me the most flexibility over my product's future. I even have a few product ideas in my backlog that would be impossible to build if I didn't maintain full end-to-end ownership of the nutrition data. If it this strategy doesn't work out and I realize I need to change course? No problem.

Next Steps

This release is just "version 1" of the Community Database. I could've spent many more months working on the database before shipping it, but I wanted to get it out into the wild to start collecting feedback from a larger group of users. I plan to continue iterating on these features as part of the next several update. If you have thoughts, suggestions, or concerns, please reach out (feedback@foodnoms.com). I'd love to hear from you.

Besides that, I've now completed 5 out of 7 things I listed in my January Post "What's Next for FoodNoms ." I still need to build notifications and get started on that Watch App!